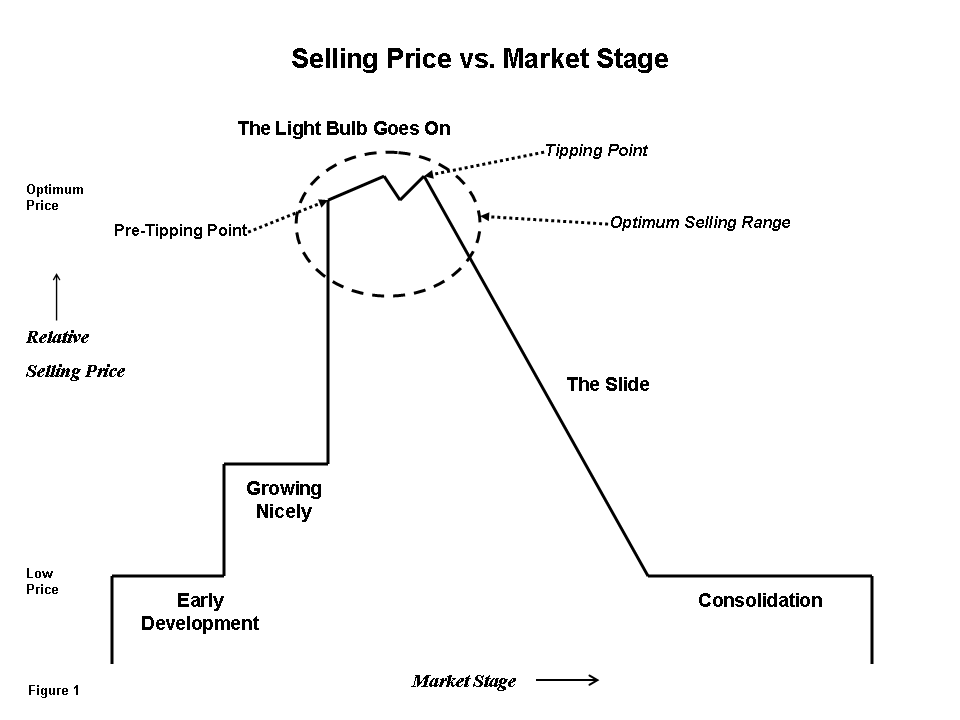

Optimum

Price vs. Market Stage

Recognizing

the pre-tipping

point of a market space is critical if a company wants to sell for the

optimum price. Why is this important? Because market timing is the

primary driver of price when selling a company. Whether it is a high

price, medium price or low price, the market timing has more influence

than any other factor.

The market may

be on a different time schedule than your company's

growth curve. If a company waits to sell until its revenues have

peaked, there may be little growth left in the company. The company has

maxed out. Buyers will realize this and will not pay top dollar. Paying

attention to the reality of the market is not only a good survival

skill, it is the primary requisite for realizing the optimum price.

The best time

to sell is when the big companies

decide to move into a

market. That is when they are willing to pay top dollar. Large

companies need to acquire technology, market knowledge and expertise in

a hurry. They want to acquire the technology, rather than develop their

own technology in order to make a speedy market entry. They also need

to acquire a company that has a team of people that understands the

market, the customers and the customers' issues.

Large

companies are rarely early movers into a new

market. Big

companies want to go into big markets, not small markets. New markets

are almost always small markets. So, until a market has clearly

demonstrated that it will be big, the large companies sit on the

sidelines and wait until they are sure that the market will be

significant. Once these larger companies do decide to move, the

pre-tipping point is at hand. Now the clock begins to tick and the

tipping point is not far behind.

Why the

pre-tipping point? Because if you wait for

the tipping point,

it will be too late. The biggest exit mistake that technology companies

make is that they decide to sell too late in the game. They want to

sell when the company has peaked. The problem is that this is usually

unrelated to market timing. This is an internal focus and an internal

focus rarely leads to the highest price. Many technology executives

ignore market timing. The highest value is achieved by looking

externally and capitalizing on the optimal market situation.

Market

Stages

The life cycle of a market consists of several

stages that are

typically illustrated by a graph showing industry revenues over time.

These stages are introduction, growth, maturity and decline. A similar

graph can illustrate the best time to sell. However, instead of the

vertical axis representing total revenues, it represents the relative

selling price of acquisitions. It is critical for a selling company to

view the market stages from this viewpoint—from the perspective of how

much a buyer is likely to pay. The stages break out like this:

- Early Development

- Growing Nicely

- The Light Bulb Goes

On

- The Slide

- Consolidation

Early

Development

In the Early

Development stage a number of smaller companies are

developing technology and scrambling to get customers. The market is

new, so there are not any medium-sized companies yet. The large

acquirers don't yet know if this market will be a significant market.

If a buyer is willing to make an acquisition at all, it will be for a

moderate price at best. Medium-sized buyers are the only buyers at this

stage because small acquisitions of less than $20 million are

meaningful to them. These buyers are situated on the edge of the market

or in an adjacent market, not in the core market.

[Click to

enlarge]

Growing

Nicely

Small

companies are expanding from $5 million in revenue to $20 million

in revenue. At this stage an intelligent buyer will pay a good price

for technology and people who have a familiarity with the market.

However, most large buyers will not make acquisitions at this stage.

They will wait until it is proven that the market is large before

moving in.

One of the

problems with the Growing Nicely stage is that most smaller

companies prefer to continue building on their own rather than be

acquired. They think the timing is premature. Most entrepreneurs are

quite independent and the idea of selling early is anathema.

Discrepancies

can arise between the goals of the entrepreneur and the

objectives of the shareholders. The company must be clear what its

goals are—to build a business and stay independent (sometimes at all

costs) or to build a business and sell at the optimal time.

If a company

is growing nicely, it usually wants to continue down this

path. The entrepreneur and his team are doing well and having fun. They

have overcome hurdles and obstacles. It feels good to be growing

nicely. They want to continue enjoying the ride. The last thing they

want to do is to sell. They view selling as "game over." If they were

to consider selling, it would be after just one more good quarter of

revenue, one more new product release, one more industry trade show,

etc. There is always something.

An ironic

situation can occur at this point. A second tier company may

not be growing quite as nicely as the company described above. It may

be having difficulty making headway in the market so it decides to sell

to a larger company on the periphery of the market. Now the second tier

player has access to the financial strength and the sales and

distribution capabilities to make major inroads. Their technology may

not be the best, but with strong sales and marketing power they can be

a potent force in the market.

The Light Bulb Goes

On

At the Light

Bulb stage the big companies finally get it. They

recognize that the market will be substantial in size. They make

acquisitions and are willing to pay top dollar.

Acquisitions

are the best way to grab a foothold in a short time

period. Competitive pressures dictate that they participate in this

market, so they follow each other into the market. They do not want to

be left out. Even a company on the edge of the market who is not a

major player may make an acquisition in order to procure software or

technology that can be part of their overall product solution.

The apex of

the graph represents the point in time when the first large

company makes an acquisition to enter the core market. This is the

pre-tipping point. A second company will soon follow with another

acquisition. Companies are realizing that this will be an emerging and

vital market. Sometimes a third company joins the fray. Rarely,

however, will there be more than three big players making acquisitions

at this stage. Sometimes a major player will make several acquisitions.

The first small or medium-sized company to sell often obtains the best

price, a kind of “first seller advantage.”

The Slide

The Slide

begins after the tipping point, after the large players have

moved in. The only reason an acquisition would be made during the Slide

phase is if a large company chose to acquire a medium-sized company in

order to add mass and shore up some of its product offerings. In this

phase the big companies are firming up U.S. operations and possibly

moving into a few foreign markets. The acquisition of an overseas

company is about the only good possibility in this stage. The large

companies have already made their acquisitions and any remaining

smaller players must settle for a smaller piece of pie.

Consolidation

In the

Consolidation phase buyers will make acquisitions primarily to

add customers. The price will not be a high one. Buyers do not need to

acquire technology or engineering teams because they already have their

own teams and technology. Even if a smaller company has truly better

software or technology, the costs of switching are too high to make an

acquisition attractive. A buyer may seek to acquire a company in a new

geographic location. Almost all acquisitions made in the Consolidation

phase are motivated by a desire to add to the customer base.

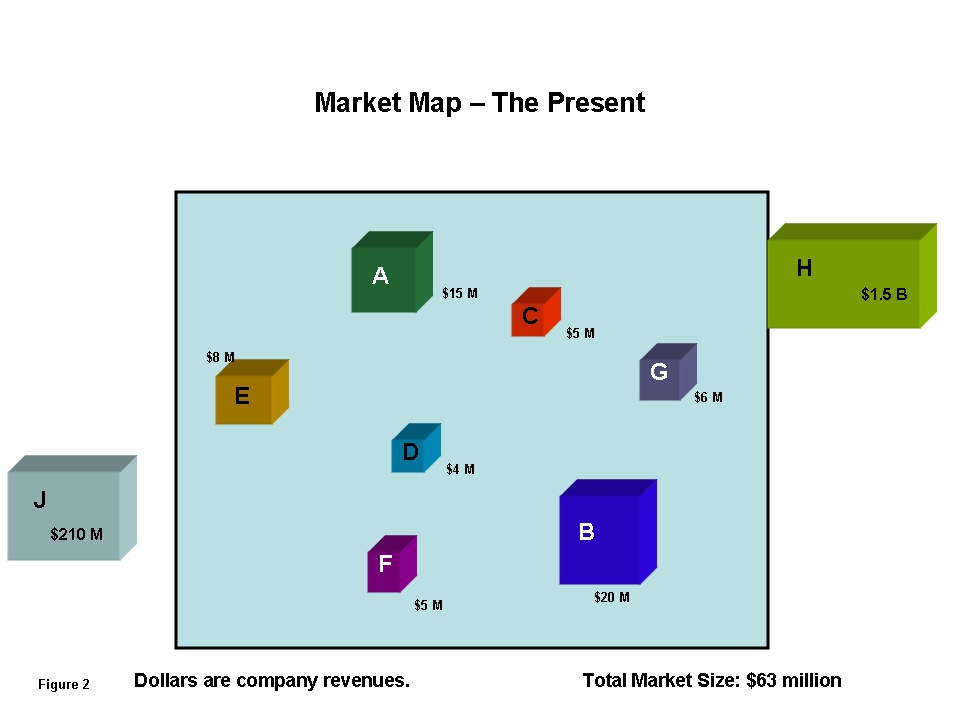

Mapping the Market

Market maps

are an excellent way to visually represent the state of the

market and the movement of that market. There are three states: the

present state, the movement and the future state. What can we learn

from looking at these diagrams?

[Click

to enlarge]

The

Present

This market

map depicts the present market situation, typically

consisting of a handful of small players. The technology is not cast in

concrete; no standards have been set. There are no big companies

because the market is too new and too small for them. However, there

are a few big companies in adjacent markets who are keeping an eye on

the pace of growth in this new market.

Many CEOs have

a myopic viewpoint, focusing only on their core market.

Their viewpoint is black and white—a buyer is regarded as either in

their market or not in their market. However, the gray edges of the

market and the adjacent markets can be fertile areas for good acquirers.

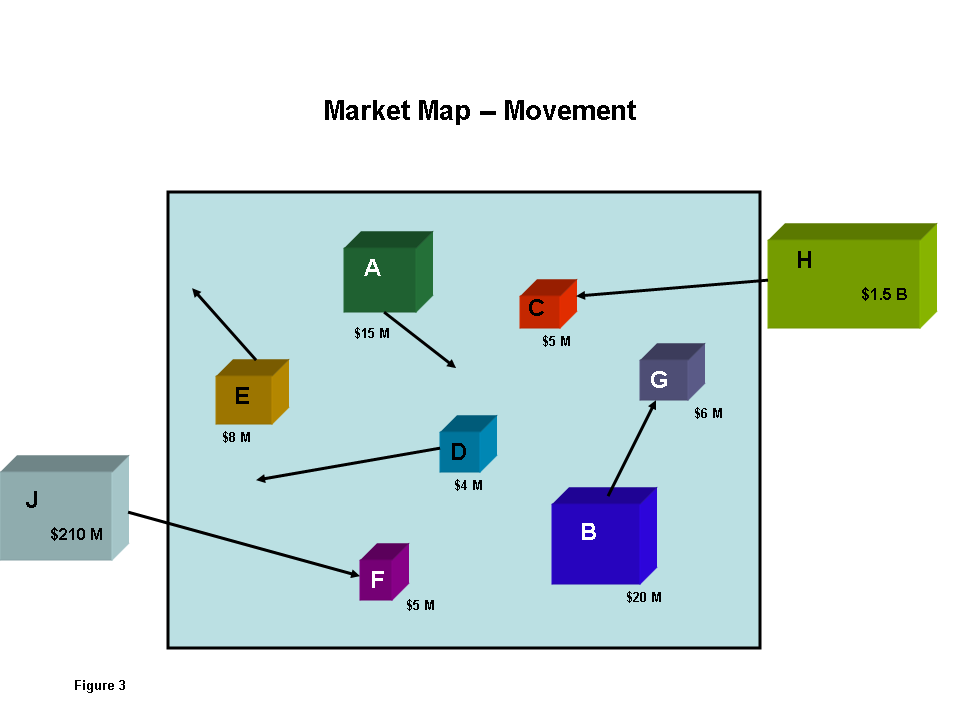

Movement

The Market

Movement Map is a dynamic map illustrating the movement of

companies into the market, making acquisitions, as well as companies

moving away from the core. This is where the market begins to morph.

Some companies are moving in, some are making acquisitions, and some

are doing both. A big company in an adjacent market is making an

acquisition. A smaller firm is moving toward the edge of the market,

deciding to focus on a particular vertical niche rather than cater to

the market as a whole.

Many companies

do not see this picture very clearly. The management

teams are busy running their companies and have their heads down,

focused on developing technology and selling product. Their focus is

operational, trying to “peddle faster,” rather than thinking about the

broader strategic picture.

[Click

to enlarge]

Medium-sized

companies rarely make acquisitions during this morphing

phase. The likely target companies are their competitors and they may

not particularly like them. They think their own technology is superior

so why would they acquire another company?

Market

bitterness may also play a role. They may have lost sales to a

competitor or heard remarks at a trade show that the competitor was

badmouthing them. These reasons may seem petty but they inhibit a

growing company from seeking an acquisition. So, they choose to grow

only organically. The downside is that a bigger company in an adjacent

market can acquire a small player and very rapidly gain a strong market

position, sometimes eclipsing the medium-sized company that was doing

fairly well in the market originally. The lesson here is—when the

market begins to morph, when the big players begin to move, a

medium-sized firm needs to take action and make an acquisition in order

to grab a bigger piece of the market. A smaller company should seek to

acquire or to be acquired or it will be left to languish.

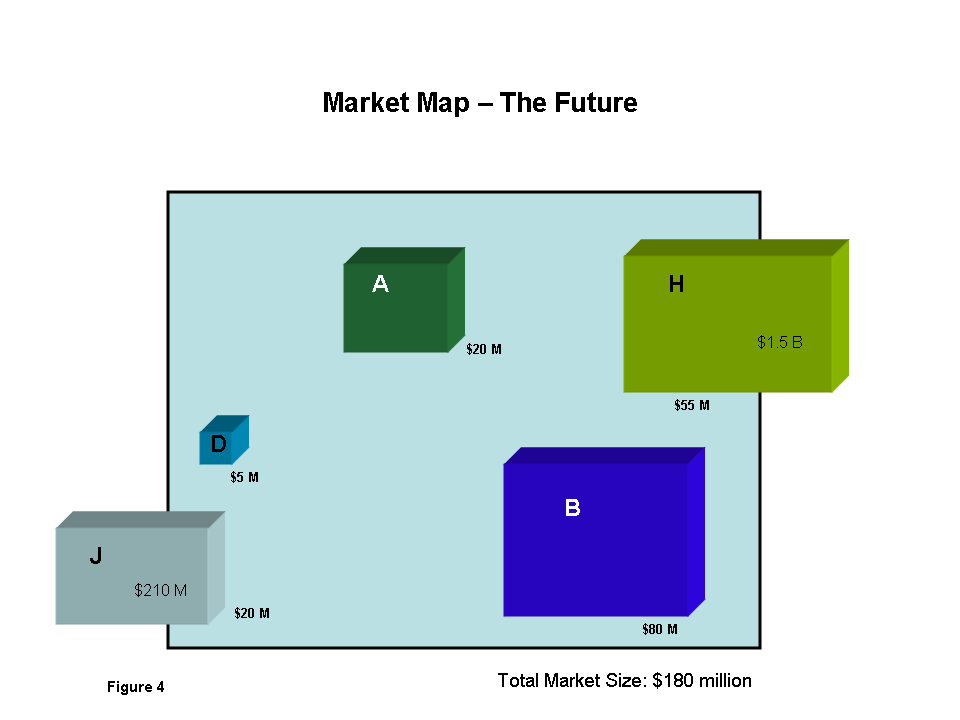

The Future

The Future

Market Map looks almost exactly the same for most market

sectors. There will be one or two market leaders and one third-place

company. If a fourth or a fifth company exists, it will be small and

will not be particularly profitable.

There are a

few other observations to make from the market maps. Notice

that Company A does not make an acquisition. It grows from $15 million

to $20 million, which is respectable, but now it is a third place

player. Company H and Company B have grown through acquisitions and

have eclipsed Company A. Notice that this market has tripled in size

from $60 million to $180 million in total revenues and is still

growing. What started out as an insignificant market is now a very

respectable market.

[Click to

enlarge]

Recognizing

the Pre-tipping Point

The first

major sign that the pre-tipping point has been reached is

when one of the large companies makes an acquisition in the core market

space. Large is a relative term—it could be a $1 billion revenue

company or it could be a $200 million revenue company. It depends on

the market, the size of the market and the relative size of the

companies in that market.

When a second

large company makes an acquisition in the space, it is

time to get moving. The tipping point is near at hand. The time period

between the first acquisition and the second acquisition could be

short, within six months or maybe a little longer, up to 18 months. But

rarely is the second acquisition any farther down the road than that.

A good example

of the pre-tipping point is the online

advertising industry. Google recently bought Double Click for $3.2

billion. A month later Microsoft acquired aQuantive inc. (which owns

Avenue A and Razorfish) for $6 billion. This deal was disclosed less

than 24 hours after WPP Group's $649 million acquisition of 24/7 Real

Media. In the time span of less than two months the three major players

have made three acquisitions. The tipping point is now at hand.

Another clue

is when a large company develops technology internally in

order to enter a new market space. If this is the case, articles and

news releases will report about the company's move into the market

sector. For example, Microsoft developed its own software for its music

player, Zune.

A large

company may contact you out of the blue about acquiring your

company. Do not dismiss the idea too readily. It may be the right

market time. If a big company has acquired, or is acquiring, one of

your competitors, it may be wise to be proactive and explore a sale to

another large competitor.

Summary

If a company

wants to sell for the optimum price, the best thing it can

do is pay attention to the stage of the market. This goes against the

instincts of may tech people who are overly focused on their own

technology. The stage of the market is the primary driver for realizing

the optimum price for the sale of a company.

|